Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 54, No 2 - Summer 2008

Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 54, No 2 - Summer 2008 Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas |

| Lithuanian Art and the

Avant-Garde

of the 1920s Vytautas Kairiūkštis and the New Art Exhibition in Vilnius |

|

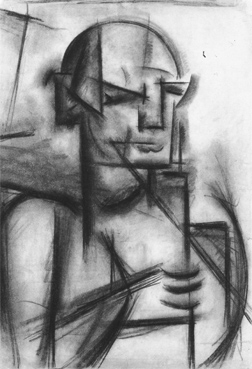

| Vytautas

Kairiūkštis, Self-portrait, drawing, 1923 |

Viktoras Liutkus

Art historian Viktoras Liutkus is a scholar of the Lithuanian Modernist era and has published monographs on Viktoras Vizgirda, Antanas Mončys and Antanas Samuolis. At present he chairs the painting department of the Vilnius Academy of the Arts.

Avant-garde trends in Lithuanian poetry and literature in the 1920s are well researched (for example the literary movement Keturi vėjai [Four Winds]) but the situation is less clear-cut for the fine arts, primarily due to the fact that the number of avant-garde works of art was small and did not result in such strong reactions and controversy among critics and the reading public as did literary works. Traditional definitions of what constitutes the avant-garde1 cannot be applied to Lithuanian artists of the 1920s because they did not engage in shocking public manifestos and radical negations of tradition. The process was much slower and more moderate. Nevertheless, efforts were made to introduce the ideas of the European avant-garde and to accelerate artistic changes in Lithuanian art of the period.

In 1909–1910, the Vilnius Art Society arranged the exhibition Trikampis (Triangle) featuring the St. Petersburg group “The Impressionists.” The exhibition was organized by the renowned Russian avant-gardist Nikolai Kulbin. In 1913, the Vilnius daily Przegląd Wileński (No. 48-49) reprinted F. T. Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism. (In Poland, it was published in October 1909 by the Krakow magazine Świat). In the same year, Przegląd Wileński printed news from the Paris Independents’ Salon, mentioning the newest painting trends: Pointilism, Cubism, and Orphism. An exhibition of the expressionists Alexander Javlensky, Mariana Veriovkina and the more moderate local Jewish painter Bencon Zukerman was organized in Vilnius in 1914-1915. Vilnius periodicals were filled with information, short articles and photographs of the latest painting trends in Paris, Berlin, Munich and St. Petersburg. Art critics used terms like Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism, although the stylistics of these trends was not yet precisely defined. Vilnius-based writers such as the Polish poet Jerzy Jankowsky, the Byelorussian poet Maxim Bahdanovich, the Jewish playwright Perec Hirsbein and others demonstrate a turning point away from Neoromanticism to expressionist experimentation, dissonanance, doubt, speed, fragmentation, a repelling city atmosphere and the figure of the “new man.” This was a reflection of local conditions and cultural changes taking place after the First World War, but it coincided with the avant-garde worldview emanating from Berlin or Munich.

New Art, starting with Cubism, became synonymous with Futurism, Suprematism, Dadaism, Purism, Neoplasticism and Constructivism, showing the quick stylistic changes in painting and their intensive diversification and fragmentation which, of course, is characteristic of avant-garde artistic experiments in all areas. New Art artists claimed that the drive for creation has always been and always will be “a desire to explore the unexplored” and follows the principle of “old inherited, new invented.” Aspects of true creativity, representing the “homo technicus” spirit of the twentieth century, were speed, invention, movement, the pulse of life and rapidly changing environments. Periodicals, for instance, were constantly publishing articles and illustrations about future cities, giant bridges, airships, tall buildings, radio and telegraph innovations, etc. Publications such as Keturi vėjai informed the public about New Art artists and involved artists in discussions about the changing relationships between the artist and society.

New Art was officially introduced to Lithuanian artists and the public in 1923 by the New Art Exhibition (in Polish: Wystawa Nowej Sztuki), which took place in Vilnius from May 20 to June 20 at the Corso Cinema on A. Mickiewicz Avenue, at approximately the same location where the Vilnius Cinema was located during the postwar Soviet era. The fact that Vilnius was under Polish governance at the time does not remove it from the history of Lithuanian art: the exhibition took place in the territory of the Republic of Lithuania, which had declared its independence before the Polish occupation, and it was organized by the efforts and with the financial support of the well-known Lithuanian painter Vytautas Kairiūkštis (1890-1961). It remains the most prominent and significant avant-garde event of the time.

The New Art Exhibition was a meeting ground for two avant-garde movements, Russian and Western European. Both Vytautas Kairiūkštis and Władyslav Strzemiński were familiar with the Russian avant-garde. Both had studied in Moscow and knew the foremost Russian avant-gardist Kazimir Malevich3. Kairiūkštis came to Vilnius in 1921 and Strzemiński, who was probably invited by Kairiūkštis, a year later. The cover design of the New Art Exhibition catalogue and its typographic style (its author was probably Kairiūkštis rather than Strzemiński), as well as the inside layout, expressed the ideas of New Art and is close to Russian Suprematism in the Malevich style, uniting Suprematism, Constructivism and Futurism.

|

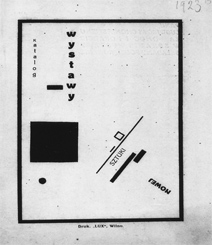

Vytautas

Kairiūkštis. Self-portrait, 1922 |

On the other hand, the participating Warsaw-based artists Mieczysław Szczuka, Teresa Żarnower and Henrik Stażewski had close ties with Western Europe and with German Constructivism. M. Szczuka and T. Żarnowerówna had already exhibited in Der Sturm Gallery in Berlin. But their works also show influences of the Russian avant-garde (V. Tatlin), Dutch Constructivism (De Stijl), and the aesthetics of French Purism. M. Szczuka, moreover, sympathized with Russian communist ideas.

The Vilnius exhibition was diverse and hosted works of painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, scenography, and printing. Cubist, Constructivist, and Suprematist compositions predominated. Kairiūkštis presented twenty-three works, the largest selection. It included three Suprematist works influenced by K. Malevich as well as several Constructionist paintings and drawings. He was obviously familiar with the theoretical works of Malevich, whose texts on Suprematism are stored in the Lithuanian artists’ archive.

|

Vytautas

Kairiūkštis, Cover design of the New Art Exhibition Catalog, 1923 |

The exhibition was meant to provoke visitors by emphasizing the differences between the exhibited works and traditional art. New Art was meant to be perceived as a negation of tradition, a statement of innovation and challenge. The term signified war on strict imitation of nature and cleansed art of its literary, mystical, historical and pseudoclassical elements, as Kairiūkštis writes in his article for the New Art Exhibition Catalog. To this end, the organizers deliberately made fun of the visitors. For instance, according to a review in Lietuvos Rytas (No. 7, 26 May 1923), a poster at the entrance to the exhibit warned visitors to acquire “special preparation” and postcards of spectacular photographed landscapes were displayed for visitors “still looking for beauty in art.” Next to them, in contrast, were placed the latest up-to-date avant-garde periodicals and books.

The reaction of Vilnius local artists and their associations was negative. As mentioned above, Vilnius art gallery goers, local artists and art critics were familiar with avant-garde manifestos and had hosted works influenced by contemporary European art trends. However, the Vilnius University’s Art School (then Stephan Batory University) was still looking back to nineteenth century traditions, and the works of Vilnius artists followed the trends of Neoclassicism (L. Slendziński), Realism (B. Kubicki), Impressionism (A. Szturman) and moderate Expressionism (St. Matusiak). The Vilnius-based Plastic Art Society (Wileńskie Towarzystwo Artystów Plastyków) responded with utter silence. Its periodical, Poludnie, made no comment on the exhibition. The members of the society were the elite of local professional painters, experienced artists who often traveled to Europe and a few of whom taught at the School of Art.

|

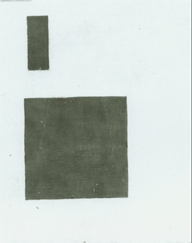

Kazimierz

Malewicz, Black and red square, ca. 1920. |

Local traditional artists also reacted with scepticism or silence. Reviews in Vilnius periodicals presented the exhibition as ”the expression of new trends in painting” and for the most part rejected it: “reach neither your mind, nor your soul,” ”why should it be called art?” (in Lietuvos Rytas, No. 2, 29 May 1923, “combinations of squares, rectangles and orbs […] do not belong to the sphere of art (“Wystawy Wileńskie,” Przegląd Wileński, No. 23, 24 June 1923). At best, there was some cautious speculation about what could come of such art. Kairiūkštis and Strzemiński published articles expressing their ideals and defending their own creations, for example Kairiūkštis in Przegląd Wileński, (10 June 1923), and Strzemiński in Zwrotnica (1923). Kairiūkštis lamented the fact that the exhibition was so unappreciated. In his letter to Paulius Galaunė in Paris, he wrote that ”newspapers disparage the exhibition” or demonstrate ”utter incomprehension.“ “We see that Vilnius is a deeply provincial town of puritans, not interested in art whatsoever.“ 4 One of his students, V. Drėma, wrote later that his mentor’s works were “not understood by the public. They were met by shoulder-shrugging, taunts, irony and mocking. [...] The distance between avant-garde art and society’s primitive understanding of plastic art was too great.“5

|

Vytautas

Kairiūkštis, Supremacist compostion, 1992–1993 |

The New Art Exhibition was not an isolated avant-garde event in Vilnius at that time. At the end of 1922, Zbignev Pronaszko, a famous modern sculptor and painter as well as author of theoretical articles (he was associated with Zwrotnica), who consequently taught scenography workshops at the School of Fine Arts, created a bold cubo-futurist model of a monument to the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz. The idea of the monument had a long history, dating back to the first announcement in Kurjer Litewski in 1905. Twelve meters high, the colossal rough-edged model, made of wooden planks and concrete, was erected in front of the Vilnius Town Hall but caused so much opposition that it had to be relocated to the right bank of the River Neris, close to the artillery buildings in Tuskulėnai. Several years later the monument was completely demolished and swept away by the river. The situation is another illustration of the reaction of Vilnius society to revolutionary ideas and radical innovations.

What was the importance of the New Art Exhibition to the Vilnius artistic community of the early twenties and to the local environment of culture and painting? Was the New Art Exhibition, in the words of one reviewer, “too early a flower“?

At first glance, the exhibition might look like merely an initiative by two talented painters to present their work. Yet, avant-garde art in Vilnius, though perhaps “too early a flower” for the local art community, appeared at exactly the right moment when seen in the context of the avant-garde movement in Europe. Negative popular reactions to avant-garde exhibitions were similar in other European cities.

|

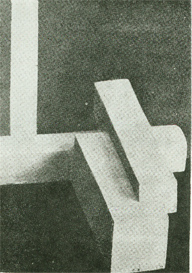

Władysław

Strzemiński, Model of the railroad station in the city of Gdynia (Gdańsk). 1923. |

New Art artists started to emerge in Eastern and Central European cities almost simultaneously and New Art exhibitions took place in Riga, Bucharest, Budapest, Prague, Warsaw, Łódź and other major cities. Numerous avant-garde periodicals were disseminating the latest up-to-date infomation and reproducing works of art. Artists were exchanging periodicals, information, and exhibition catalogs. The catalog for the New Art Exhibition was found in the archive of the famous Hungarian avant-gardist L. Kossak. The exhibition earned Vilnius its 47 name as one of the true avant-garde cities of Eastern Europe in the 1920s and for a short period made the city a place for the Constructivist Manifesto.

The New Art Exhibition has been noted in many Polish and Lithuanian art history publications and catalogs as a substantial turn in the arts of both countries.6 It was a stimulus for the emergence of avant-garde groups, uniting three Vilnius-based artists, Vytautas Kairiūkštis, Władyslav Strzemiński, and Maria Puciatycka7, with four Warsaw-based artists, Henrik Stażewski, Meczysław Szczuka, Karol Kryński and Teresa Żarnoverόwna (Żarnower). It offered an impulse to further development of Polish Constructivism. Thus, a group of Polish Constructivists Blok (The Bloc), was founded that included the participants of the New Art Exhibition. Kairiūkštis was a member and participated in the first exhibition of the group in Warsaw in 1924; his works were reproduced in the Blok newsletter. The group arranged exhibitions in Warsaw, Riga, Brussels, and Bucharest and was the basis for the formation of the later Praesens (Present Tense) group (1926), which V. Kairiūkštis also had links with.

The exhibition was a precondition for many European avant-garde links and cooperation between avant-garde artists. During his trip to Italy in 1924, Kairiūkštis met the famous Italian Futurists F. Marinetti and E. Prampolini and viewed their works, although he was not very impressed by Futurism and its ideas. The contacts between the avant-garde artists formed in the twenties continued. Polish publications cite a letter from the Polish avant-gardist Wł. Strzeminsky to Kairiūkštis (9 January 1927), in the archives of avant-garde researcher A. B. Nakov in Paris, in which he writes about his efforts to create a collection of New Art (Constructivism), an idea first raised during his common activity with V. Kairiūkštis in Vilnius. Such a collection was eventually formed and exhibited in a Łódź museum in 1931. Today it is one of the most significant collections in the museum. In 1928, Wł. Strzemińsky organised in Warsaw the Modernist Salon exhibition, including one of Kairiūkštis’s paintings. It was moved to Vilnius and exhibited in the Railway Workers Club that November. H. Stażevski asked Kairiūkštis to help organize the exhibition, reminding the latter that he was still a member of the group and could act under its name (presumably, Stażevsky had Blok in mind).

Kairiūkštis himself remained faithful to Constructivism throughout the thirties. He enters the history of Lithuanian art with his avant-garde artwork, his theoretical articles on Constructvism, and his impact on his students (V. Drėma and V. Macutkevičius). Kairiūkštis ran a painting studio in Vilnius and taught at the Lithuanian Vytautas Magnus Gymnasium until 1928. In 1928, the international literary and art journal MUBA (in Paris) included two issues edited by Lithuanian poet Juozas Tysliava and published articles on New Art and reproductions of artworks by Vytautas Kairiūkštis as a Constructivist. The Lithuanian typography also demonstrated some radical changes.

With the New Art Exhibition, the newest avant-garde trends of the times – Constructivism and Suprematism – began to emerge in Lithuania. The New Art concept in the ideological programs of the twenties included many trends in various art spheres: painting, literature, architecture, design, posters, theater and printing, marking the emergence of the most modern art phenomenon of the twentieth century in Lithuania and the dissemination of avant-garde ideas in Vilnius. It enters the history of Lithuanian painting as the first prominent challenge to the previous tradition of national art. The exhibition was a manifestation of the simultaneous adoption of European art trends and marked a spread of avant-garde ideas in the country. The Constructivist, Suprematist works of V. Kairiūkštis, his participation in the exhibition and his efforts to organise it, enable us to state that the avant-garde entered Lithuanian art at precisely the right time. All this shows that ideas of the European avant-garde left their mark on Lithuanian art.

WORKS CITED

Baranowicz, Z. Polska awangarda artystyczna. 1918–1939, Warszawa, 1975.

Constructivism in Poland 1923 to 1936, Kettle’s Yard Gallery in association with Museum Sztuki, Łódź [Catalog], 1984.

Drėma, V. “Mūsų plastinė dailė,” Lietuviškas baras, No. 12, 1938.

Kairiūkštis, Vytautas. Tapyba. Piešiniai. Katalogas. Lietuvos dailės muziejus, 1990.

Keturakis, S. Avangardizmas XX amžiaus lietuvių poezijoje. Vilnius: Vilnius University Press, 2002.

Kvietkauskas, M. “Ekspresionizmo ženklai XX a. pradžios Vilniaus literatūrose,” Literatūra, 2003, No. 45(1).

Mansbach, S.A. Modern Art in Eastern Europe. From the Baltic to the Balkans. Ca. 1890-1939. Cambridge, 1999.

Наков, A. Беспредметный мир. Абстрактное и конкретное исскуство. Россия и Полъша. Москва. Исскуство, 1997.

Poklewski, J. Polskie życie artystyczne w międzywojennym Wilnie, Toruń, 1994.

Présences Polonaises, Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou[Catalog], 1983.

Rozważania o smaku artystycznym. Studia pod redakcją Józefa Poklewskiego i Tomasza F. De Bosset. Toruń, 2002.

Striogaitė, D. Avangardizmo sukūryje. Lietuvių literatūra. 3-asis dešimtmetis. Vilnius: Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore 1998.

Turowski A. Konstruktyvizm Polski. Próba rekonstrukcji nurtu. 1921–1934. Wrocław 1981.

W 70 rocznicę Wystawa Nowej Sztuki. Museum Sztuki, Łódź [Catalog], 1993.

Zagrodzki, Janusz. Katarzyna Kobro i kompozycja przestrzeni. Warszawa, 1984.